Return to Albion - Sissinghurst

If I were asked to name one garden that exemplifies everything about the evolution of not only horticulture, but of the very nature of 20th century life in England, it would have to be Sissinghurst Castle Garden. A vast and varied property with roots in Tudor England, once a manor, then a ruin, and finally a life-long project for a modernist who was both a Victorian and a pioneer, it deserves its international reputation. Located in the rolling hills of Kent, Sissinghurst basks in some of the best growing conditions on the island. It encompasses more than 450 acres and has the advantage of scale; the fact that for many years it was in private hands, means that it never has the feel of a garden designed by committee.

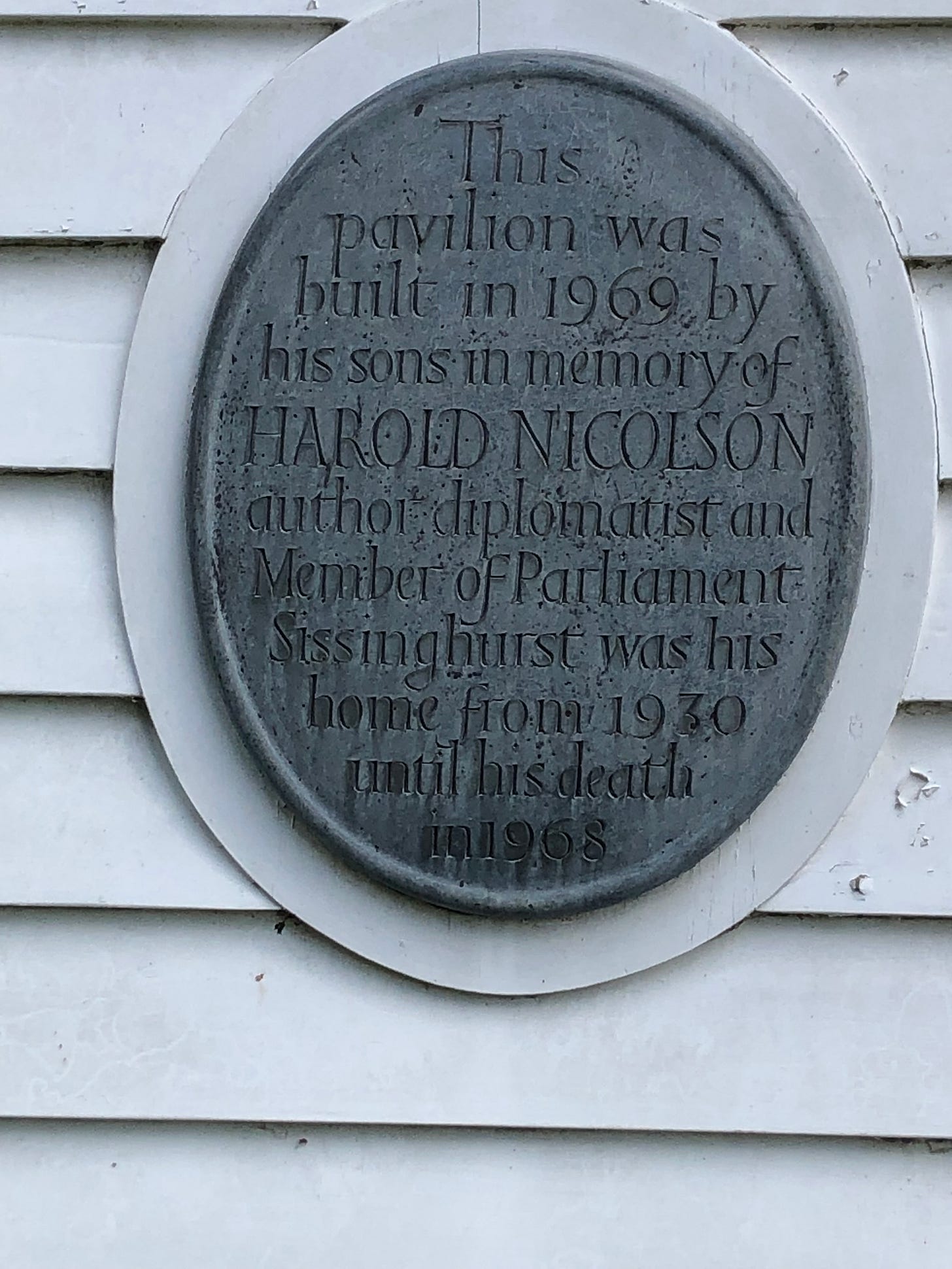

Vita Sackville-West’s story, and her reputation as a stern polymath, is well documented. Cheated out of her ancestral home (Knole) by primogeniture or some such archaic rule, married to Harold Nicholson, in a relationship with Virginia Woolf, writer, designer and founding member of the National Trust’s Garden committee. Her articles in The Observer helped educate a generation of post-war gardeners eager to make the most of their suburban patches. But make no mistake, throughout the century, and against the tide of history, Vita and Harold’s passion was the creation of Sissinghurst.

At first glance, it’s hard to imagine that the various buildings making up the house would give confidence to a gardener looking to recreate a lost inheritance. This is no grand manor in the form of Castle Howard or Blenheim, but rather a collection of tumble-down buildings contrasted by a fairly stunning tower. Like Great Dixter, this would be a hard place to live and almost immediately upon purchase in 1932 they hired architect A. R. Powys to make the place habitable. He also installed many of the walls that would come to help shape the oft-copied garden room concept. It’s these garden rooms—diverse, tidy, and impressive—that draw the crowds.

It would be impossible to do justice to the entirety of such a great garden, with thoughtful nooks at every turn and immaculate grooming throughout, so I’ll just touch on some highlights.

The Courtyards and Castle

The entrance to the garden takes you immediately through the main living spaces and face-to-face with the tower and into the geographical center of the garden—turn right and you enter the Rose Garden, turn left and you’ll find the White Garden. This is a relaxed set of borders that surround a pleasant pair of lawns. Dominating the space is the impressive Tower which keeps you oriented throughout your visit.

The White Garden

Stumbling upon the White Garden is a bit like seeing the Mona Lisa or the Statue of Liberty in that it is simultaneously underwhelming and somehow stunning. Everyone knows about it, most of us have copied it, but its real beauty lies in the complexity. There’s an almost stump-the-band quality to the number of “alba” cultivars that seem to exist and the gardeners make good use of the subtleties of color, texture and structure of a tightly limited palette. We spent nearly an hour in this relatively small space and it was clear that they knew how important it was to get this right. They do, and it’s a joy.

Delos

Once described in 1990’s National Trust book as “the most perplexing and least satisfactory part of Sissinghurst” this Mediterranean garden has come into its own with a recent renovation. Delos is a large, dry gravel garden perched alongside a traditional English manor—a sort of La Defense to Sissinghurst’s Paris. But it makes perfect sense as Vita and Harold’s first garden was near Constantinople and it seems fitting that they’ve decided to bring it up to top form.

The Wilder Spaces

Outside the many types of garden rooms that define Sissinghurst there exists a number of less curated gardens that are just as charming as the signature spaces. The Orchard is one of the largest areas in the cultivated portion and gives you a welcome break from the formality and allow you to look back on the house and towers and get a sense of proportion. The Nuttery showcases an overwhelming number of low groundcovers protected by a canopy of hazels, filberts, and viburnums. Most surprising were the pastures and woods that make up the remaining portion of the estate. With 5 acres of cultivated gardens you have more than 440 acres that you are free to wander at your leisure. Rambling through the farm and its rolling hills you get a real sense of the Kentish countryside.

As I read this it seems that I’m less than enthusiastic about Sissinghurst, but nothing could be further from the truth. It delivers everything you would want in a great garden: imagination, attention to detail, and a sense of history. A grand day out for any enthusiast. And sure, the National Trust bugbear of homogenizing some of the public spaces (and menus) still holds true, but where would we be without them. In fact, even with Vita’s years of work with the NT she was adamant that Sissinghurst never be given over to the organization. It was only when the realities and burdens of owning such an expensive and extensive property became clear to her son Nigel that in 1966 it became a public treasure.